| |

|

CS 3723

Programming Languages

|

Activation Records

Functions & Recursion |

[Note: All parts of this page use integer features of MIPS.]

Activation Records in General.

If one properly uses a stack at runtime to support function calls,

this approach implements recursion "for free", without any additional

effort. At run time, each called function is supported by an

activation record, which is storage on the stack dedicated

to that particular call of that specific function.

The MIPS architecture gives minimal hardware support for

recursive functions, so everything must be done "by hand".

The activation record needs to provide storage (at runtime) for at

least the following items:

- The return address (address from which the function was called).

A function might be called from any number of places, including

from within itself (recursive call) from any number of places.

- The value returned by the function

(which might be a pointer).

- Locations to hold values of actual parameters fed

to the function. (These can be expressions.) After the function is

called, these locations function as the formal parameters.

They behave like local variables.

- Space for (non-static, automatic) local variables

used by the function.

The work below uses a running example of a function of two

parameters: a "raise-to-a-power" function. This has two parameters

and doesn't require any local variables besides registers, so the

activation record will hold 4 items, as shown in the illustration below.

(The order of these items was an arbitrary choice.)

This diagram shows the stack before the function is called.

The "stack pointer", denoted by $sp, points to one

location beyond the top of the stack, that is, it points to the

first available location. Since we are working with doubles, we

will only consider 8-byte items on the stack, although the return

address takes up only 4 bytes.

[The diagrams show the special MIPS "stack pointer" $sp

used to access the MIPS system stack. This is what one would

normally use. In order to avoid any possible problems with

the official stack pointer, I chose to allocate storage on

a user-defined stack pointer, using the register $s2 for it.

We have been using $s1 to save the return address

of our MIPS function main.]

In the diagram below, the stack pointer "old $sp" might be pointing

to the bottom of the stack, with nothing below it. Alternatively,

which is below will be the mostly recently called function that is

still active (has not yet returned). Assume that the next thing

to do is to call a function (in fact a pow or rtp function).

The old $sp calculates the

two actual parameters, and inserts them into the stack, into locations

that will be part of the activation record of the function to be called.

These locations are shown in red below.

Stack for Activation

Records: Before Function Is Called,

First Insert Parameter Values |

|---|

STACK

| | | Next (recursive)

|--------------| | Activation

| | | Record

===|==============|=== -------+

old -24 ---> | Insert P2 | |

|--------------| | Space for Next

old -16 ---> | Insert P1 | | Activation

|--------------| | Record

old -8 ---> | | | (or first one)

|--------------| |

old $sp ---> | | |

===|==============|=== -------+

old +8 ---> | Parameter 2 | |

|--------------| | Previous (current)

old +16 ---> | Parameter 1 | | Activation

|--------------| | Record

old +24 ---> | Return value | | (if present)

|--------------| |

old +32 ---> | Return addr | |

===|==============|=== --------+

|

After the function is called (control is passed to the function),

the function first allocated an activation record on the stack,

in this example by decrementing the $sp by 32

($sp = $sp - 32).

(This stack is growing toward smaller memory locations.)

The function can now "find" the values of actual parameters

at known offsets. These locations become the formal parameters

for the function. First the function inserts its return address

into the activation record (MIPS gives access to this return address).

Then the function does its computations, ending with a value

to return, which is inserted into the activation record.

During its execution, the function may have called other functions,

and each of those will push additional activation records onto the

stack. By the time this function returns, all other called functions

will have returned, so there is nothing above the current activation

record. Finally, the called function deletes (deallocates) its

activation record by incrementing $sp by 32. The function then

returns control to the place from which is was called.

[It's important to realize that there is only one register $sp.

"Old" and "new" above refer to different values stored in the

register at different times.]

Stack for Activation

Records: Function Executes,

Insert RetAdd, Calculate and Insert Return Value |

|---|

STACK

| | | Next (recursive)

|--------------| | Activation

| | <--- new $sp | Record

===|==============|=== -------+

old -24 ---> | Parameter 2 | <--- new +8 |

|--------------| | New (current)

old -16 ---> | Parameter 1 | <--- new +16 | Activation

|--------------| | Record

old -8 ---> | Insert RetVal| <--- new +24 |

|--------------| |

old $sp ---> | Insert RetAdd| <--- new +32 |

===|==============|=== -------+

old +8 ---> | Parameter 2 | |

|--------------| | Old (previous)

old +16 ---> | Parameter 1 | | Activation

|--------------| | Record

old +24 ---> | Return value | | (if present)

|--------------| |

old +32 ---> | Return addr | |

===|==============|=== --------+

|

Now, as shown below, the calling function can access the value returned

by the function that it called. The calling function will usually

have its own activation record (as shown), but it is the main

function, it will have no activation record.

Stack for Activation

Records: After Function Returns,

Retrieve Return Value |

|---|

STACK

| | | Next (recursive)

|--------------| | Activation

| | <--- new $sp | Record

===|==============|=== -------+

old -24 ---> | Parameter 2 | <--- new +8 |

|--------------| | Old deallocated

old -16 ---> | Parameter 1 | <--- new +16 | Activation

|--------------| | Record

old -8 ---> |Retrieve RetV | <--- new +24 |

|--------------| |

old $sp ---> | Old RetAdd | <--- new +32 |

===|==============|=== -------+

old +8 ---> | Parameter 2 | |

|--------------| | Current (restored)

old +16 ---> | Parameter 1 | | Activation

|--------------| | Record

old +24 ---> | Return value | | (if present)

|--------------| |

old +32 ---> | Return addr | |

===|==============|=== --------+

|

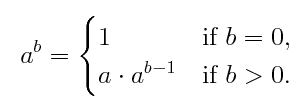

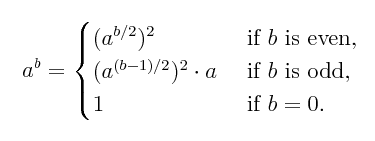

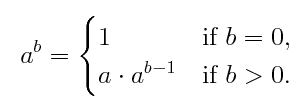

Our Specific Example: c = a ^ b.

We will start with a simple pow function:

The table on the right below shows a Python function to do the

calculation using a loop, and another function using recursion

and based on the definition above.

The table on the right below shows a Python function to do the

calculation using a loop, and another function using recursion

and based on the definition above.

| Python a^b Functions |

Output |

# atob.py: find c = a^b

import sys

def pow0(a, b): # loop

c = 1

while b != 0:

c = c*a

b = b - 1

return c

def powr(a, b): # recursion

if b == 0:

return 1

return a*powr(a, b-1)

def powd(a, b): # recursion debug

if b == 0:

res = 1

else:

res = a*powd(a, b-1)

output("Call: ", a, b, res)

return res

def output(s, a, b, c):

sys.stdout.write(s + "a:%.17g" % a)

sys.stdout.write(", b:%.17g" % b)

sys.stdout.write((", a^b:%.17g" % c)

+ "\n")

a = float(raw_input( "-->" ))

b = float(raw_input( "-->" ))

c = pow0(a, b)

cr = powr(a, b)

output("Loop: ", a, b, c)

output("Recurs: ", a, b, cr)

# cd = powd(a, b) # only for 7^10, .9^7

# output("debug: ", a, b, cd) # ditto

| % python atob.py

-->7

-->10

Loop: a:7, b:10, a^b:282475249

Recurs: a:7, b:10, a^b:282475249

Call: a:7, b:0, a^b:1

Call: a:7, b:1, a^b:7

Call: a:7, b:2, a^b:49

Call: a:7, b:3, a^b:343

Call: a:7, b:4, a^b:2401

Call: a:7, b:5, a^b:16807

Call: a:7, b:6, a^b:117649

Call: a:7, b:7, a^b:823543

Call: a:7, b:8, a^b:5764801

Call: a:7, b:9, a^b:40353607

Call: a:7, b:10, a^b:282475249

debug: a:7, b:10, a^b:282475249

-->1.6180339887498949

-->28

Loop: a:1.6180339887498949, b:28, a^b:710646.99999859335

Recurs: a:1.6180339887498949, b:28, a^b:710646.99999859335

-->2

-->31

Loop: a:2, b:31, a^b:2147483648

Recurs: a:2, b:31, a^b:2147483648

-->0.9

-->7

Loop: a:0.90000000000000002, b:7, a^b:0.47829690000000014

Recurs: a:0.90000000000000002, b:7, a^b:0.47829690000000014

Call: a:0.90000000000000002, b:0, a^b:1

Call: a:0.90000000000000002, b:1, a^b:0.90000000000000002

Call: a:0.90000000000000002, b:2, a^b:0.81000000000000005

Call: a:0.90000000000000002, b:3, a^b:0.72900000000000009

Call: a:0.90000000000000002, b:4, a^b:0.65610000000000013

Call: a:0.90000000000000002, b:5, a^b:0.59049000000000018

Call: a:0.90000000000000002, b:6, a^b:0.53144100000000016

Call: a:0.90000000000000002, b:7, a^b:0.47829690000000014

debug: a:0.90000000000000002, b:7, a^b:0.47829690000000014

|

Now I want to code these by hand into MIPS.

I want to take input variables a and b,

calculating a^b,

and leaving the result in a variable c. However, in order to

keep things simpler and shorter, I'm not using any memory locations

below for variables, but I'm only using registers and the

activation records. How the double registers are used

is shown in the first table on the left below.

The MIPS program pow0.s on the left below shows a very simple loop to

calculate a^b, using the register conventions. The MIPS program

powr.s on the right uses recursion instead of a loop. This program

uses a single sequence of recursive calls, so that at the end

we can see all the activation records that were used. (None of

the storage was overwritten during execution. In more complex

programs, the stack of activation records might grow and shrink

many times.) The diagram on the left below shows the

11 activation records used to calculate 7^10, at levels

0 (the first one), through 10.

| Variables to Registers |

|---|

# mapping of variables to registers:

# $f0 (used for input)

# a = $f2

# b = $f4

# c = $f6 (at end c=a^b)

# 0 = $f8 (constant)

# 1 = $f10 (constant)

# $f12 (used for output)

# $f14 (for return value)

# 2 = $f16 (constant)

# $f18 (temporary)

#

# $s1 (address of M)

# $s2 (address of stack)

|

| Level |

Activation

Records for 7^10 |

|---|

| P 2 | P 1 |

Return Value | Ret Addr |

| 10 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 4194656 |

| 9 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 4194656 |

| 8 | 2 | 7 | 49 | 4194656 |

| 7 | 3 | 7 | 343 | 4194656 |

| 6 | 4 | 7 | 2401 | 4194656 |

| 5 | 5 | 7 | 16807 | 4194656 |

| 4 | 6 | 7 | 117649 | 4194656 |

| 3 | 7 | 7 | 823543 | 4194656 |

| 2 | 8 | 7 | 5764801 | 4194656 |

| 1 | 9 | 7 | 40353607 | 4194656 |

| 0 | 10 | 7 | 282475249 |

4194396 |

| |

| a^b, with simple loop |

|---|

### pow0.s: calculate c = a^b

main: addu $s7, $ra, $zero

# addr of M: constants, vars, temps

la $s1, M

# read a as double

li $v0, 7

syscall

mov.d $f2, $f0

# read b as double

li $v0, 7

syscall

mov.d $f4, $f0

### end reading, start processing

l.d $f8, 0($s1) # 0.0

l.d $f10, 8($s1) # 1.0

l.d $f6, 8($s1) # c=1

WhileStart0:

c.eq.d $f4, $f8 # if b==0

bc1t WhileEnd0 # goto

mul.d $f6, $f6, $f2 # c=c*a

sub.d $f4, $f4, $f10 # b=b-1

j WhileStart0

WhileEnd0:

### return to system

addu $ra, $s7, $zero

jr $ra

.data

.align 3

M: .double 0.,1.

Blank: .asciiz " "

NewL: .asciiz "\n"

|

<−− Red at left = return to main.

|

| a^b, recursive |

|---|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76 |

### powr.s: act. records and recursion

main: addu $s7, $ra, $zero

# addr of S, M: stack, constants

la $s2, S stack (act recs)

la $s1, M const 0.0, 1.0

### start of compiled code

# 2 constants

l.d $f8, 0($s1) # 0.0

l.d $f10, 8($s1) # 1.0

# read a as double, store as param1

# in the activation record

li $v0, 7

syscall

s.d $f0, -16($s2)

# read b as double, store as param2

# in the activation record

li $v0, 7

syscall

s.d $f0, -24($s2)

# call function

jal pow

l.d $f14, -8($s2) # ret val

# print return value, obtained

# from the activation record

li $v0, 3

l.d $f12, -8($s1)

syscall

# print NewL as ASCII char

li $v0, 4

la $a0, NewL

syscall

# return to system

addu $ra, $s7, $zero

jr $ra

########## body of pow function #######

pow:

# push activation record

addi $s2, $s2, -32

# save return address on stack

sw $ra, 32($s2)

# load parameters from activation record

l.d $f2, 16($s2) # a

l.d $f4, 8($s2) # b

# main part of function

l.d $f6, 8($s1) # c=1

# check for end to recursion

c.eq.d $f4, $f8 # if b==0

bc1t RecursEnd

# get ready for recursive call

sub.d $f4, $f4, $f10 # b=b-1

# insert 1st and 2nd parameters

s.d $f2, -16($s2) # a

s.d $f4, -24($s2) # b-1

# call function (recursive)

jal pow

l.d $f14, -8($s2) # ret val

# multiply value returned by a

mul.d $f6, $f14, $f2 # c=c*a

RecursEnd:

# insert return value

s.d $f6, 24($s2)

# restore return address from stack

lw $ra, 32($s2)

# pop activation record

addi $s2, $s2, 32

# return

jr $ra

######### end of pow function #########

.data

.align 3

T: .space 1000

S:

M: .double 0.,1.

Blank: .asciiz " "

NewL: .asciiz "\n"

Tab: .asciiz "\t"

|

Overview of execution:

main: 8-21, call pow

pow: repeat 10 times: 36-55

call pow recursively

each time push one AR

pow: 36-48, 61-67, push last AR

return from pow to pow

pow; repeat 10 times: 56-67

multipy by a; delete one AR

return from pow to pow

main: return to main to after call to pow.

22-35, print ans, return to system

|

| |

| Trace of pow, inputs 7.0 and 10.0 |

|---|

| | Lines | Action |

Synbols |

|---|

m

a

i

n |

| 8-9 | Load constants 0.0, 1.0 |

$f8=0.0; $f10=1.0 |

| 12-19 | Read inputs: 7.0, 10.0

Store as params into AR0 |

AR0[0]=10.0;

AR0[1]=7.0; |

| 21 | Call pow |

jal pow |

| | | |

A

R

0 |

| 36 | Start executing pow |

pow: |

| 38 | Allocate AR0 (includes 2 params) |

|

| 40 | Save return address in AR0 |

AR0[3] = $ra |

| 42-43 | Load params from AR0 into regs

7.0 into $f2, 10.0 into $f4 |

$f2=AR0[1];

$f4=AR0[0]; |

| 45 | Load 1.0 into $f6, value to return |

$f6=1.0 |

| 47 | Check $f4 (== 10.0) against 0.0 |

$f4!=0.0 |

| 48 | do NOT branch to RecursEnd |

continue at line 50 |

| 50 | Subtract 1 from $f4 |

$f4=$f4-1;

($f4==9.0) |

| 52-53 | Store params (7.0,9.0) into AR1 |

AR1[1]=$f2 (==7.0)

AR1[0]=$f4 (==9.0) |

| 55 | Call pow recursively |

jal pow |

| |

A

R

1 |

| 36 | executing pow again | pow: |

| 38-55 | Same as before, except:

AR0 ==> AR1; AR1 ==> AR2;

10.0 ==> 9.0; 9.0 ==> 8.0 | |

| Act Recs: AR2 through AR9, with 8.0 through 1.0 |

A

R

1

0 |

| 36 | executing pow again | pow: |

| 38-47 | Similar to before, except:

AR9 ==> AR10; 1.0 ==> 0.0; | |

| 48 | DO branch to RecursEnd (line 59).

Do NOT call pow |

RecursEnd: |

| 61 | Insert return value into AR10[2] |

AR10[2]=$f6 |

| 63 | Restore return address from AR[3] |

$ra=AR10[3] |

| 65 | Delete current activation record |

|

| 67 | Use $ra above to return. |

jr $ra |

| | | |

A

R

9 |

| 56 | return to just after call to pow | |

| 56 | return to just after call to pow

load return value from AR10[2] |

$f14 = AR10[2]; |

| 58 | mult ret value by a, store in $f6 |

mul.d $f6,$f14,$f2 |

| 61 | Insert ret value into act rec |

AR10[2]=$f6 |

| 63-67 | Just as above |

|

Act Recs: AR8 down to AR0, mul-->t by 7.0 each time.

Last return goes back to line 22 in main program. |

m

a

i

n |

| 22 | Load ret value from AR0 into $f12 |

| 25-27 | Print return value |

| 29-31 | Print newline |

| 31-35 | Return to system |

|

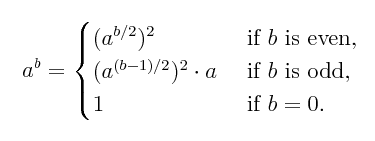

Fancy Exponentiation.

This example uses a more complex raise-to-a-power algorithm,

given by the equations below. Here the recursion is essential, unless

one completely rewrites the algorithm. However, again in this

case there is only a single tower of recursive calls, so that

a dump at the end again shows all the activation records.

At the end are two tables showing them for example runs.

| Python a^b Functions |

Output |

# atob_fancy.py: find c = a^b

import sys

def atob(a, b): # formula

if b == 0:

return 1

if b%2 == 0:

return atob(a, b/2)**2

return atob(a, (b-1)/2)**2 * a

def atobd(a, b): # debug version

if b == 0:

res = 1

elif b%2 == 0:

res = atobd(a, b/2)**2

else:

res = atobd(a, (b-1)/2)**2 * a

output("Call: ", a, b, res)

return res

def output(s, a, b, c):

sys.stdout.write(s + "a:%.17g" % a)

sys.stdout.write( ", b:%.17g" % b)

sys.stdout.write((", a^b:%.17g" % c)

+ "\n")

a = float(raw_input( "-->" ))

b = float(raw_input( "-->" ))

c = atob(a, b)

output("Fancy: ", a, b, c)

sys.stdout.write("\nDebug version:\n")

c = atobd(a, b)

output("Debug: ", a, b, c)

| % python atob_fancy.py

-->1.6180339887498949

-->57

Fancy: a:1.6180339887498949, b:57, a^b:817138163596.00073

Debug version:

Call: a:1.6180339887498949, b:0, a^b:1

Call: a:1.6180339887498949, b:1, a^b:1.6180339887498949

Call: a:1.6180339887498949, b:3, a^b:4.2360679774997898

Call: a:1.6180339887498949, b:7, a^b:29.034441853748636

Call: a:1.6180339887498949, b:14, a^b:842.99881375871053

Call: a:1.6180339887498949, b:28, a^b:710646.99999859312

Call: a:1.6180339887498949, b:57, a^b:817138163596.00073

Debug: a:1.6180339887498949, b:57, a^b:817138163596.00073

-->2

-->973

Fancy: a:2, b:973, a^b:7.9833612381388792e+292

Debug version:

Call: a:2, b:0, a^b:1

Call: a:2, b:1, a^b:2

Call: a:2, b:3, a^b:8

Call: a:2, b:7, a^b:128

Call: a:2, b:15, a^b:32768

Call: a:2, b:30, a^b:1073741824

Call: a:2, b:60, a^b:1.152921504606847e+18

Call: a:2, b:121, a^b:2.6584559915698317e+36

Call: a:2, b:243, a^b:1.4134776518227075e+73

Call: a:2, b:486, a^b:1.997919072202235e+146

Call: a:2, b:973, a^b:7.9833612381388792e+292

Debug: a:2, b:973, a^b:7.9833612381388792e+292

|

Below is the recursive version of this program translated to

MIPS using activation records as in the previous program.

| a^b, Fancy

Algorithm |

|---|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52 |

### rtp.s: use activation records

main: addu $s7, $ra, $zero

# addr of S, M: stack, constants

la $s2, S stack (act recs)

la $s1, M const (0,1,2)

# 3 constants

l.d $f8, 0($s1) # 0.0

l.d $f10, 8($s1) # 1.0

l.d $f16, 16($s1) # 2.0

# read a as double, store as param1

li $v0, 7

syscall

s.d $f0, -16($s2)

# read b as double, store as param2

li $v0, 7

syscall

s.d $f0, -24($s2)

# call function

jal rtp

# get return value

l.d $f14, -8($s2)

# print return value

li $v0, 3

l.d $f12, -8($s1)

syscall

# print NewL as ASCII char

li $v0, 4

la $a0, NewL

syscall

# return to system

addu $ra, $s7, $zero

jr $ra

######### body of rtp function ####

rtp:

# push activation record

addi $s2, $s2, -32

# save return address on stack

sw $ra, 32($s2)

# load parameters

l.d $f2, 16($s2) # a

l.d $f4, 8($s2) # b

# start main part of function

l.d $f6, 8($s1) # c=1

# check for end to recursion

c.eq.d $f4, $f8 # if b==0

bc1t RecursEnd

|

# next check for even b

div.d $f18, $f4, $f16 # t1 = b/2

trunc.w.d $f18, $f18 # trunc(b)

cvt.d.w $f18, $f18 # to double

mul.d $f18, $f18, $f16 # mult by 2

sub.d $f18, $f4, $f18

c.eq.d $f18, $f8 # res comp to 0

bc1f BisOdd

# here b is non-zero and even

# get ready for recursive call

div.d $f4, $f4, $f16 # b = b / 2

# insert 1st and 2nd parameters

s.d $f2, -16($s2) # a

s.d $f4, -24($s2) # b/2

# call function (recursive)

jal rtp

l.d $f14, -8($s2) # return val

# square return value, result in c

mul.d $f6, $f14, $f14 # c = ret^2

b RecursEnd

BisOdd:

# here b is non-zero and odd

# get ready for recursive call

sub.d $f4, $f4, $f10 # b = b - 1

div.d $f4, $f4, $f16 # b = b / 2

# insert 1st and 2nd parameters

s.d $f2, -16($s2) # a

s.d $f4, -24($s2) # (b-1)/2

# call function (recursive)

jal rtp

l.d $f14, -8($s2) # return val

# square return value, result in c

mul.d $f6, $f14, $f14 # c = ret^2

# multiply by a

mul.d $f6, $f6, $f2

RecursEnd:

# insert return value

s.d $f6, 24($s2)

# restore return address from stack

lw $ra, 32($s2)

# pop activation record

addi $s2, $s2, 32

# return

jr $ra

######### end of rtp function ###########

.data

.align 3

T: .space 1000

S:

M: .double 0.,1.,2.

Blank: .asciiz " "

NewL: .asciiz "\n"

|

| Level |

Activation

Records for 2^973 |

|---|

| P 2 | P 1 |

Return Value | Ret Addr |

| 10 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4194720 |

| 9 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4194720 |

| 8 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 4194720 |

| 7 | 7 | 2 | 128 | 4194720 |

| 6 | 15 | 2 | 32768 | 4194688 |

| 5 | 30 | 2 | 1073741824 | 4194688 |

| 4 | 60 | 2 | 1.15292150e+18 | 4194720 |

| 3 | 121 | 2 | 2.65845599e+36 | 4194720 |

| 2 | 243 | 2 | 1.41347765e+73 | 4194688 |

| 1 | 486 | 2 | 1.99791907e+146 | 4194720 |

| 0 | 973 | 2 | 7.98336123e+292 | 4194400 |

| Red = return to main. |

| L | Activation

Records for φ^57 |

(Return Value)/sqrt(5) |

|---|

P

2 | P

1 |

Return Value | Return

Address |

| 6 | 0 | φ | 1 | 4194720 |

0.4472135954999579≐F(0)=0 |

| 5 | 1 | φ | 1.6180339887498949 | 4194720 |

0.7236067977499789≐F(1)=1 |

| 4 | 3 | φ | 4.23606797749978981 | 4194720

| 1.8944271909999157≐F(3)=2 |

| 3 | 7 | φ | 29.0344418537486355 | 4194688

| 12.984597134749391≐F(7)=13 |

| 2 | 14 | φ | 842.998813758710526 | 4194688

| 377.0005305032323≐F(14)=377 |

| 1 | 28 | φ | 710646.999998593121 | 4194720

| 317811.0000006294≐F(28)=317811 |

| 0 | 57 | φ | 817138163596.000732 | 4194400

| 365435296162.0003≐F(57)=365435296162 |

Here is a python program (using high precision floats) that gives more

accurate values for the last two floats above

(see mpmath):

| φ^28 and

φ^57 |

|---|

% python power.py

from mpmath import *

import sys

mp.dps = 80

print "Precision: ", mp.dps

mp.dps = 100

print "Precision: ", mp.dps

five = mpf(5)

phi = (1 + sqrt(five))/2

print "phi: ", phi

print "phi**200: ", phi**200

print "F(200): ", phi**200 / sqrt(five)

python power.py

Precision: 80

phi: 1.618033988749894848204586834365638117720309179805

phi^28: 710646.9999985928316027479464165778158308091807432

phi^57: 817138163596.0000000000012237832530049452374054045

F(57) : 365435296161.9999999999994527074913110237343018279

1 2 3 4 5

12345678901234567890123456789012345678901234567890

|

|